The Swine Health Information Center, launched in 2015 with Pork Checkoff funding, protects and enhances the health of the US swine herd by minimizing the impact of emerging disease threats through preparedness, coordinated communications, global disease monitoring, analysis of swine health data, and targeted research investments.

The Swine Health Information Center annually solicits input for its Plan of Work which guides its activities each year. The 2026 Plan of Work is currently under development and will be built around SHIC’s five strategic priorities: 1) improving swine health information, 2) monitoring and mitigating risks to swine health, 3) responding to emerging disease, 4) surveillance and discovery of emerging disease, and 5) swine disease matrices. These priorities, developed through stakeholder input, will guide the 2026 Plan of Work, implemented by Executive Director Dr. Megan Niederwerder and Associate Director Dr. Lisa Becton with input from the SHIC Board of Directors and SHIC Working Groups.

Stakeholder input for SHIC’s 2026 Plan of Work can be submitted here and is requested by December 1, 2025. Input may include topic areas, research priorities, and/or identified industry needs that will focus SHIC’s programmatic and research efforts in 2026, such as an emerging swine disease or an emerging swine health issue. Broad input is encouraged and invited to help inform priorities for broad producer value and benefits to swine health.

While SHIC’s activities are guided by the Plan of Work, the organization remains nimble and responsive to industry needs as they arise throughout the year. As challenges to swine health and production continuously change, stakeholders are encouraged to provide input and ideas year-round to address newly identified needs.

As a recent example, the development of the H5N1 Risk to Swine Research Program highlights how SHIC adapted its Plan of Work to directly address needs associated with this emerging disease. This aligns with SHIC’s mission, which is to protect and enhance the health of the US swine herd by minimizing the impact of emerging disease threats through preparedness, coordinated communication, global disease monitoring, analysis of swine health data, and targeted research investments.

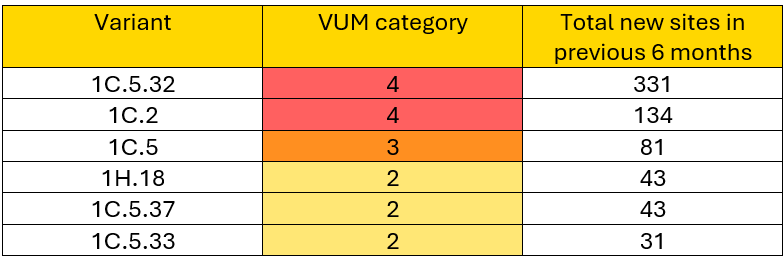

A new national surveillance effort enhances decision-making in swine health by identifying and communicating emerging PRRSV variants. Dr. Mariana Kikuti, recently appointed assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, is leading the development of the PRRSV Variants Under Monitoring (VUMs) Monthly Report in collaboration with the SHIC-funded Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project and the PRRS-Loom analytical platform. The report, launched in August 2025, is designed to give producers and veterinarians an early warning of potential threats, improving preparedness and coordinated response across the industry.

This initiative utilizes the PRRS-Loom tool, a machine-learning model that analyzes 603 ORF5 bases to classify viruses by lineage, sublineage, and variants. These classifications are combined with a forecasting algorithm that anticipates whether a variant is likely to expand significantly, defined as more than a 20% increase in the next year, based on retrospective data with 77% accuracy (Pamornchainavakul et al., 2024). When integrated with the near real-time MSHMP data, the approach allows the new report to identify where specific PRRSV variants are already present and estimate their potential for wider spread.

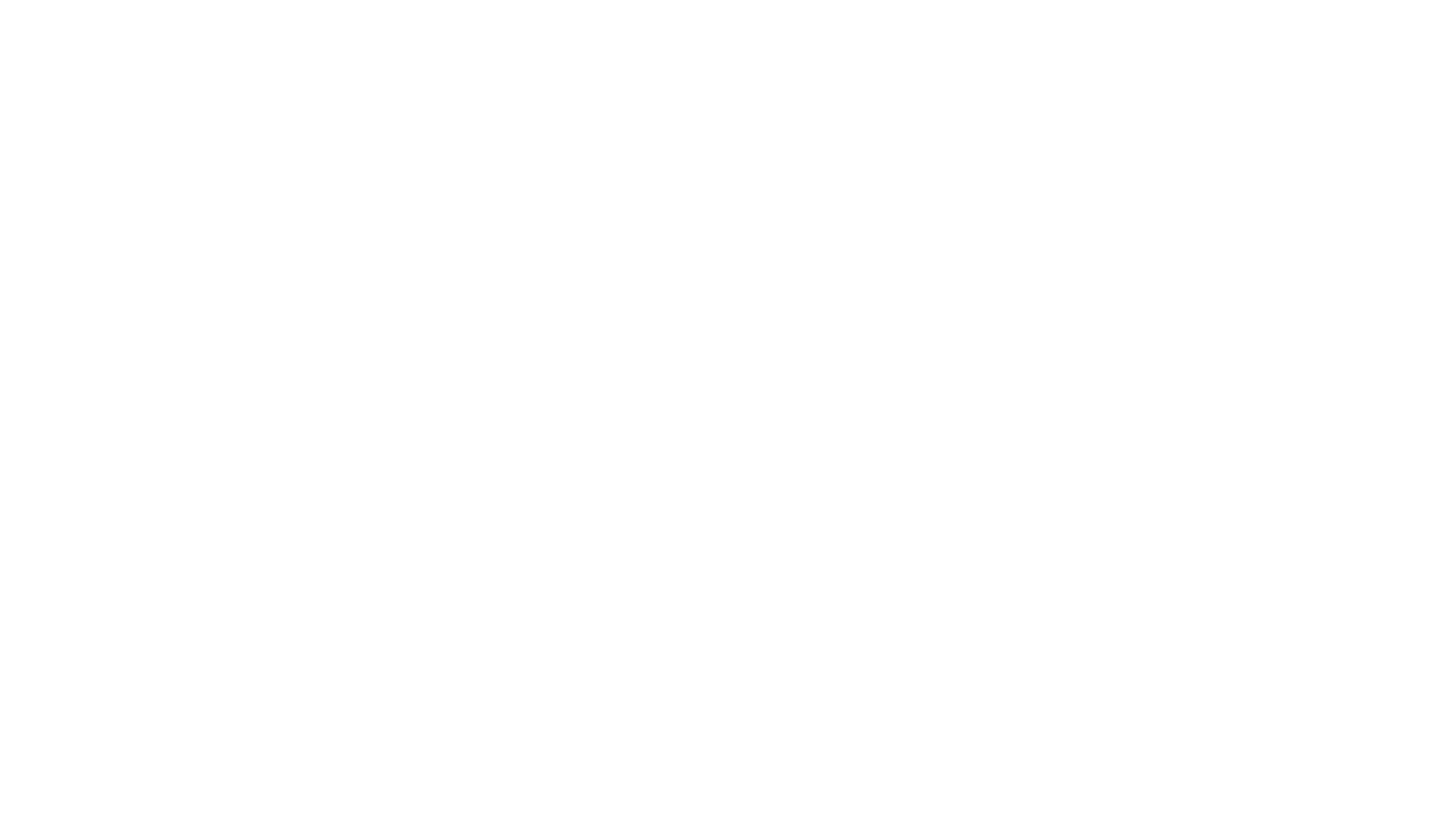

PRRSV variants are defined as closely related viruses based on ORF5 gene similarity, typically differing less than 2.5% within a variant and 5% from the nearest related variant. VUMs specifically represent PRRSV-2 variants circulating in the US that show genetic and epidemiologic indicators of wider transmission. To highlight urgency and guide responses, VUMs are categorized into four levels according to the number of sites impacted over the past six months:

Reports for Level 2 or higher VUMs will include expanded epidemiological discussion, examining affected sequences, sites, systems, and states. These summaries will be accompanied by epidemiological curves showing variant dynamics over time and situation reports that provide context for ongoing industry response. Together, these tools give stakeholders greater situational awareness, helping veterinarians and producers adjust strategies before a variant reaches wider distribution.

Dr. Kikuti and her team are committed to making this information broadly accessible and focused on actionable information for producers. The VUM reports will be circulated to MSHMP participants, shared in SHIC’s monthly e-newsletter, and made publicly available on both the MSHMP website and the PRRS-Loom platform.

A study funded by the Swine Health Information Center Wean-to-Harvest Biosecurity Research Program, in partnership with the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research and Pork Checkoff, evaluated the effectiveness of a waterless trailer decontamination method using modified vaporous hydrogen peroxide (mVHP) in combination with an industrial vacuum system. The study, conducted by Dr. Erin Kettelkamp, Swine Vet Center, evaluated the effects of the vacuum plus mVHP on PEDV detection and inactivation using varying disinfectant contact times. Results showed that mVHP treatment paired with a vacuum system reduced the relative PEDV viral load via PCR detection on contaminated trailers while no difference was detected between contact times. Further research is needed to assess the impact of this technology on virus inactivation and its potential application and scalability in the field.

Find the industry summary for project #24-003 here.

Effective biosecurity protocols for swine transport are critical to controlling endemic pathogens like PEDV and preparing for foreign animal diseases such as African swine fever. The combination of an industrial vacuum and mVHP treatment presents a promising alternative to traditional trailer sanitation methods. Unlike current wash and thermo-assisted drying and decontamination procedures, this system is portable, waterless, and scalable, significantly reducing labor, infrastructure, and water usage associated with existing practices. This technology may be particularly valuable during disease outbreaks, when the rapid and thorough biocontainment of contaminated swine transport vehicles is critical.

Current trailer disinfection methods involving power washing, chemical disinfectants, and TADD are labor-intensive, water-dependent, and impractical for rapid or mobile deployment during disease outbreaks. The study of mVHP, which has been used successfully in military and biosafety level 4 laboratory settings due to its effectiveness in neutralizing biological agents across diverse materials without equipment degradation, shows promise. Hydrogen peroxide-based aerosol disinfectants have previously been shown to inactivate swine pathogens in work done by Dr. Kettelkamp. However, broader adoption of hydrogen peroxide-based disinfectants in swine production requires further research and optimization for field conditions. Effective field implementation of mVHP disinfection requires prior removal of organic material, such as using a portable industrial vacuum system described herein.

For this pilot study, two scenarios were evaluated: 1) mock-swine trailer under in-vitro conditions (i.e., chamber) and 2) mock-swine trailer under field-simulated conditions (i.e., shroud). For the second scenario, a miniature insulated trailer shroud was designed to mimic conditions for potential field application. A miniature aluminum trailer model was contaminated with PEDV fecal inoculum in both scenarios. An industrial-grade vacuum was used to remove organic material, followed by applying mVHP treatment across different contact times.

PEDV inoculum (USA/NC49469/2013; 10⁴ TCID₅₀/mL) was mixed with feces and shavings to prepare the contamination material. Aluminum trailer models (1:16 scale) were contaminated with PEDV fecal inoculum and treated with mVHP for 30, 60, or 120 minutes. Four replicates per treatment duration were performed, with positive controls held at ambient temperature.

Pre-marked trailer surfaces were sampled before and after treatment to confirm PEDV contamination and to assess differences in PEDV RNA detection via quantitative PCR. Bioassays were conducted via oral inoculation with post-treatment environmental samples, utilizing liquid that was recovered from the trailer after treatment. Pigs were observed for clinical signs and evidence of PEDV infection to determine if the virus had been inactivated with each treatment. The main effects of disinfectant treatment and contact time, as well as their interaction, were assessed.

Overall, study results demonstrated that application of mVHP following vacuum removal of bulk material reduced detectable levels of PEDV RNA as measured by PCR from contaminated trailer surfaces compared to untreated controls. No differences in PEDV detection levels via PCR Ct values were observed across different contact times. Further, similar numerical results were observed between the chamber and shroud scenarios.

The antiviral efficacy of mVHP treatment against PEDV could not be determined, as all environmental trailer samples failed to produce PEDV infection under in-vivo conditions, including the positive controls. All pigs remained clinically healthy during the bioassays and tested negative for PEDV infection. Limitations in virus viability and bioassay sensitivity warrant refinement in inoculum preparation and validation to ensure accurate assessment of disinfection efficacy for virus inactivation.

In this pilot study, mVHP treatment of contaminated trailers showed a reduction of detectable PEDV genetic material via PCR. The impact of mVHP treatment on PEDV infectivity was inconclusive; therefore, additional research is needed to validate virus inactivation capabilities and to improve the standardization of contamination methods to optimize bioassay procedures. With continued development, this approach could play an important role in improving transport biosecurity and disease outbreak response readiness for the swine industry.

Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research

The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR) builds public-private partnerships to fund bold research addressing big food and agriculture challenges. FFAR was established in the 2014 Farm Bill to increase public agriculture research investments, fill knowledge gaps and complement the U.S. Department Agriculture’s research agenda. FFAR’s model matches federal funding from Congress with private funding, delivering a powerful return on taxpayer investment. Through collaboration and partnerships, FFAR advances actionable science benefiting farmers, consumers and the environment.

Swine Health Information Center

The Swine Health Information Center, launched in 2015 with Pork Checkoff funding, protects and enhances the health of the US swine herd by minimizing the impact of emerging disease threats through preparedness, coordinated communications, global disease monitoring, analysis of swine health data, and targeted research investments. As a conduit of information and research, SHIC encourages sharing of its publications and research. Forward, reprint, and quote SHIC material freely. For more information, visit http://www.swinehealth.org or contact Dr. Megan Niederwerder at [email protected] or Dr. Lisa Becton at [email protected].

Funded by the Swine Health Information Center, in collaboration with the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research, a study entitled, “Epidemiology of JEV in Australian Intensive Piggeries,” has recently revealed important lessons learned from the 2021-2022 Australian experience with Japanese encephalitis virus. Led by Dr. Brendan Cowled of Ausvet Pty Ltd, the study sought to understand how and why JEV spread in Australian pigs and make recommendations to assist the US industry in preparedness should JEV ever arrive in the US, a highly relevant effort due to similarity in production methods and environmental conditions for mosquito vectors in the two countries. Among outcomes were key lessons identified to help the US swine industry respond and adapt to a potential JEV outbreak. The research focused on understanding the transmission and epidemiology of JEV within farms and assessed farm-level risk factors for JEV in the Australian outbreak using quantitative and qualitative approaches for data collection and analysis.

Find a summary of project #25-053 here.

JEV is a mosquito-transmitted virus that impacts domestic swine industries and human health. It can lead to severe production impacts in commercial swine, including reproductive failure, reduced conception, abortion, mummified and stillborn piglets, shaker piglets, deformed and weak piglets, prolonged gestation and boar infertility. The virus is present in the western Pacific and Asia but has not been identified in the US, where it poses an emerging risk to pork production.

Recommendations for US industry preparedness and response to JEV

The investigators have proposed a comprehensive suite of recommendations in their full report. These are divided into preparation for a possible outbreak, response to a confirmed outbreak and what to do if JEV becomes established in the US. However, they detail important recommendations that could be considered by swine farmers and industry largely in advance of any JEV outbreaks to enhance preparedness:

In the event of JEV becoming established in the US, it may be possible to develop machine learning or other AI approaches to predict the occurrence of seasonal JEV outbreaks. These should be developed if JEV is established to provide early warnings, allowing proactive application of surveillance and control activities such as mosquito mitigation (e.g., insecticidal use) or vaccination of breeding stock (if/when a vaccine becomes available).

Quantitative Assessment

For the quantitative approach, industry, environmental, and meteorological data were used to quantify measurable disease outcomes, identify patterns, correlations and risk factors. Further, artificial intelligence (machine learning) was used to provide real time predictive models for early identification of future JEV outbreaks. The study period included in the risk factor analysis was from July 3, 2021, to March 25, 2023, well before and after the outbreak occurred in Australian piggeries.

Researchers analyzed data from six JEV-affected sow units at both the individual sow- and site-levels. Sow-level information included the site at which they were housed (sow unit), parity, farrowing and service dates, outcomes of service (i.e., farrowed, repeat mating, etc.) and details on litters produced by successful matings. The outcome variable for the site level analysis included the weekly rate of services that resulted in four or more mummies at farrowing.

Initial outbreak investigations highlighted that heterogeneity of reproductive outcomes over time could be indicative of JEV infection. Clinical prevalence rates varied from 13.4% to 43.0% in affected sows. Notably, mummified fetuses were the most common clinical sign observed. Mummified fetuses were used as the case definition for the site-level risk factor analysis as it appeared to be an accurate indicator of JEV infection. Using mummies within the analysis was also supported by the qualitative study in which the only clinical sign reported by 100% of pig veterinarians as being present was excessive mummified fetuses in a litter. The lack of consistency for other clinical signs may be due to management or reporting.

In addition, land cover types (inland wetlands, grasslands, farmlands), elevation, and hydrological accumulation using count-based models were evaluated to investigate incidence rate ratios. Implementing machine learning, the researchers developed a model to predict high-risk periods for JEV using a broad range of real-time climatic and environmental variables.

Results showed climatological factors relevant to bird ecology were associated with an increased JEV risk. Statistically significant risk factors included long-term cumulative rainfall, mean proportion of inland wetlands, and the service month, including their interactions. For example, inland wetlands became a risk factor when interacting with increased rainfall. Conversely, more temperate grasslands offered protection, even with heavier rain.

The study demonstrated the predictive power of the machine learning model as an early warning system, accurately forecasting the timing of JEV outbreaks in severely affected sites. In the process, the team identified key influential predictors for the model, such as minimum temperature and cumulative rainfall. Further research on the machine learning model could include a composite outcome (i.e., not just mummified fetuses), and incorporation of later data from the 2025 JEV outbreak, which would increase the generalizability of the model.

Qualitative Assessment

For the qualitative approach, interviews were conducted with experts from the Australian swine industry involved in the 2022 outbreak to capture unrecorded data observations and understandings. Qualitative methods are considered particularly valuable for understanding how individuals interpret and respond to emerging situations. In the context of the Australian JEV outbreak, this approach provides a nuanced view of how veterinarians and others navigated the challenges and made decisions in rapidly evolving circumstances.

The interview participants included 11 veterinarians, two industry professionals, and two medical entomologists who were all involved in the response to the Australian outbreak. Veterinary participants represented a broad range of swine production systems within Australia. This included the two largest swine farming integrator companies collectively managing over 90,000 sows and veterinarians serving various smaller swine operations. Participants located in different areas experienced the outbreak in varied ways.

Key findings included the significant role of environmental and farm management factors influencing transmission, variability in clinical presentations and prevalence across farms, and barriers to timely detection, diagnosis and control. Early detection and effective mosquito control on farms were identified as critical components for mitigating future outbreaks and minimizing economic impacts. The Australian experience demonstrates that JEV introduction can occur without clear warning, with the virus silently circulating among birds and mosquitoes and infecting people for months before being detected in domestic swine.

One of the key challenges observed during the Australian outbreak was the variability in clinical presentation across infected farms. Participants noted that the clinical signs, severity, and timing of disease onset did not consistently align with literature descriptions or with other farms. While classic signs such as reproductive failure in sows and boars and neurological signs and deformities in piglets were observed on many farms, other farms displayed only mild or subclinical cases, which went undetected until antibody assays were conducted.

Further, the extent of disease was not uniform within or between herds – some animals were severely affected (50 – 60% of litters affected) while others were subclinical or exhibited very mild signs. Infected gestating sows showed no clinical signs until they farrowed. While initial surges in cases often declined rapidly after four to six weeks, some herds saw impacts for 10 to 12 weeks. These variable clinical presentations, combined with their subclinical nature until sows farrowed, highlight the challenge of detecting JEV infections early based solely on clinical signs. This is particularly true in completely naïve populations, where sows show no outwards signs of illness, and the first indication may be the sudden appearance of congenital abnormalities at birth.

Once JEV was detected, farm management practices focused on minimizing the impact of the outbreak through supportive animal care and vector control. Animal management strategies were primarily aimed at supporting affected animals and mitigating long-term reproductive impacts. A key management strategy employed by many of the participants was to rest affected sows for at least one estrus cycle before re-mating. Participants observed that rested sows showed significantly better reproductive outcomes compared to those that were mated immediately post-farrowing. In contrast, boars affected by infertility were often culled without time to recover, primarily due to the immediate need to increase breeding capacity. However, farms that chose to retain affected boars reported mixed outcomes; while some boars regained fertility after at least 70 days, others remained infertile.

Without a vaccine approved for swine, mosquito control emerged as the central pillar of the swine farm response in Australia. Producers relied on emergency permits and off label use while facing supply shortages as demand from the swine industry and public health programs exceeded availability. While chemical control is essential, it should not be the sole focus, and an integrated pest management approach is required. For example, environmental measures such as removing standing water, managing vegetation, and using biological larvicidal agents (e.g., Bacillus spp.), chemical larvicides (e.g., aquatain) or insect growth regulators (e.g., methoprene) proved highly effective in controlling mosquito populations on swine farms. Mechanically ventilated systems were more effective at excluding mosquitoes. In the US, integrating routine mosquito control into farm biosecurity standards should be a key activity in preparedness and prevention.

Once JEV is introduced into a new country, endemicity is likely to occur given local mosquito and bird populations can maintain virus circulation. Therefore, rather than aiming for eradication or containment, it may be more practical for the swine industry to implement sustainable management practices from the outset. Australia experiences point to a focus on maintaining vigilance through ongoing surveillance for early detection of JEV emergence in mosquito, bird, or feral swine populations, integrating mosquito control into routine farm operations, ensuring access to veterinary insecticides, repellents and vaccines, and using accurate and reliable diagnostic tools. Human vaccination and bite avoidance measures to reduce the risk of infection in people should also be prioritized.

As JEV’s global range expands due to changing weather and migratory patterns, Australia’s experience offers critical lessons for commercial swine industries like the US. This study offers invaluable insights to help the US swine industry prepare for, respond to, and adapt to a potential JEV outbreak, ultimately reducing economic impacts and safeguarding herd health.

Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research

The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR) builds public-private partnerships to fund bold research addressing big food and agriculture challenges. FFAR was established in the 2014 Farm Bill to increase public agriculture research investments, fill knowledge gaps and complement the U.S. Department Agriculture’s research agenda. FFAR’s model matches federal funding from Congress with private funding, delivering a powerful return on taxpayer investment. Through collaboration and partnerships, FFAR advances actionable science benefiting farmers, consumers and the environment.

Swine Health Information Center

The Swine Health Information Center, launched in 2015 with Pork Checkoff funding, protects and enhances the health of the US swine herd by minimizing the impact of emerging disease threats through preparedness, coordinated communications, global disease monitoring, analysis of swine health data, and targeted research investments. As a conduit of information and research, SHIC encourages sharing of its publications and research. Forward, reprint, and quote SHIC material freely. For more information, visit http://www.swinehealth.org or contact Dr. Megan Niederwerder at [email protected] or Dr. Lisa Becton at [email protected].

The Allen D. Leman Swine Conference, an annual educational event for the global swine industry, will take place September 20-23, 2025, at the RiverCentre in St. Paul, Minnesota. Swine veterinarians, pork producers, and other swine professionals will convene to attend the Leman Conference and learn the latest information and research outcomes in swine production, biosecurity, and animal health management. The Swine Health Information Center, a Leman Conference Program Partner, will have an informational display near the registration desk at the event. Drs. Megan Niederwerder and Lisa Becton will each chair breakout sessions sponsored by SHIC, covering both on-farm and transport biosecurity.

On Monday, September 22, 2025, the main conference breakout session entitled “Opportunities for on-site biosecurity practices,” is scheduled from 3:30 – 5:00 p.m. The session is sponsored by SHIC and Dr. Megan Niederwerder will serve as chair. Presentations for this session include:

Environmental contamination in dead boxes and composting bins of wean-to-finish farms

Dr. Igor Paploski, University of Minnesota

Airborne biosecurity: Comparison of air filtration and an electrostatic precipitator technology

Mark Schwartz, University of Minnesota and Schwartz Farms

Uncovering the gaps: Insights from PRRS outbreak investigations

Dr. Christine Mainquist-Whigham, Pillen Family Farms and DNA Genetics

On Tuesday, September 23, 2025, the main conference breakout session entitled “Addressing the market hog trailer biosecurity challenges,” is scheduled from 10:30 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. The session is sponsored by SHIC and will be chaired by Dr. Lisa Becton. Presentations for this session include:

Trailer contamination and re-contamination

Dr. Cesar Corzo, University of Minnesota

Market hog trailer cleaning and disinfection: An economic and epidemiologic assessment

Dr. Ben Blair, University of Illinois

A production system approach to optimizing transport biosecurity, economics, and health

Jeremiah Mallard, Christensen Farms

Coordinated communication and broad dissemination of swine health information is one of SHIC’s main priorities. Working with the Leman Conference team offers the opportunity to expand SHIC’s reach by sharing outcomes from work conducted because of the Center’s research priorities. In addition to the sponsorships and chairing sessions, SHIC’s display table provides the opportunity to offer information and connect with Conference participants.

This month’s Domestic Swine Disease Monitoring Report adds information on a new pathogen: Escherichia coli genotype PCR. A bonus page and podcast explain the E. coli data. PRRSV overall case positivity decreased, remaining below 20% as expected for the summer period. However, PRRSV case positivity is still above the expected levels in Iowa and Minnesota. PEDV case positivity also remains low, but in the wean-to-market category, there was a moderate increase in positive cases, raising concern for biosecurity in finishing sites. Influenza A case positivity achieved the lowest percentage (18%) since 2010, highlighting that IAV detection is below the expected levels compared with historical data. Finally, in the confirmed tissue diagnosis from Iowa State University, there was a moderate increase in the number of Sapovirus cases detected. In the podcast, Dr. Marcelo Almeida, assistant clinical professor and diagnostician at ISU, discusses the recent E. coli PCR genotype trends, the main E. coli virotypes and pathotypes, and tips for E. coli control on farms.

In the Global Swine Disease Monitoring Report, African swine fever was detected in Estonia, where the virus was confirmed on the country’s largest pig farm in a farrowing unit housing around 27,000 pigs, accounting for nearly 45% of Estonia’s pig production. In Egypt, a new foot-and-mouth disease serotype, SAT-1, was detected, adding to the country’s existing endemic serotypes SAT-2, O, and A. The illicit movement of animal products was pronounced in August where detection at points of entry into Indonesia, US, and Malaysia are described. Authorities in Indonesia detained 800 kg of wild boar meat shipped without proper documentation. In Los Angeles, 6,682 lbs of mislabeled animal products from China were seized from a repeat offender. Additionally, the report highlights the seizure of 114 tonnes of pig carcasses and 640 tonnes of smuggled pork products in Malaysia in early 2025.

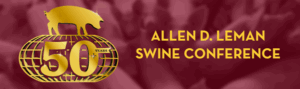

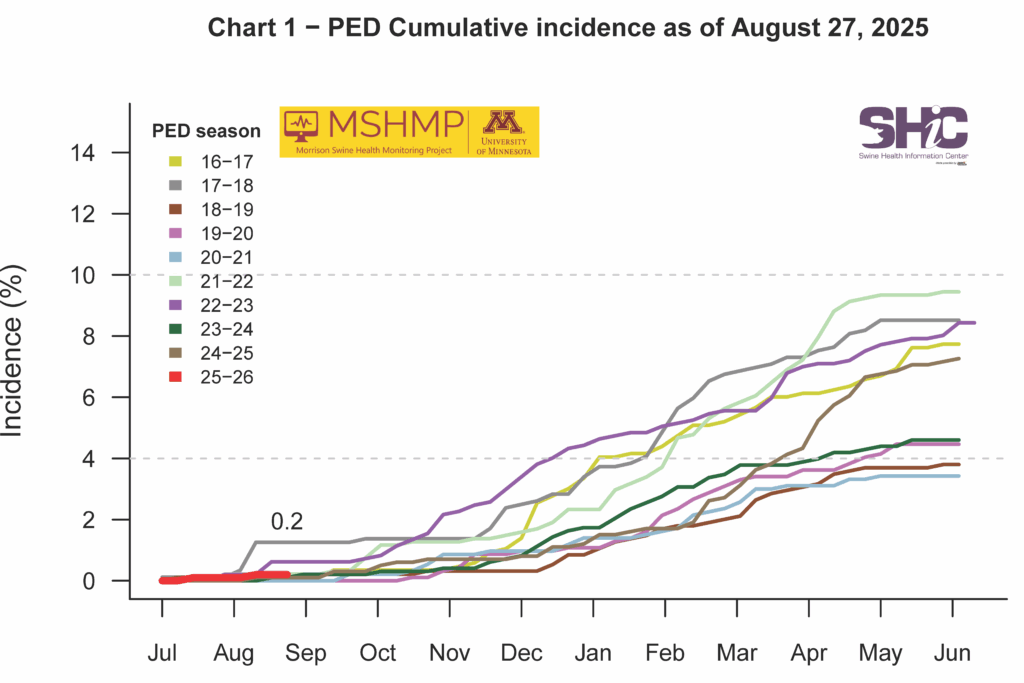

PRRS Cumulative Incidence for MSHMP

PEDV Cumulative Incidence for MSHMP

Six PRRSV variants were classified as Variants Under Monitoring (VUMs) category 2 or higher and are described in this month’s report. Variants 1C.5.32, 1C.2, and 1C.5 have been detected in over 10 states, while variants 1H.18, 1C.5.37, and 1C.5.36 have been detected in five to six states. Variant-specific situation reports are available for all six variants.